What a difference a few hours of driving makes. We left chilly Trogon Lodge up in the country’s highest mountain range to head south out of the central mountain range to the hot and steamy lowlands of the Osa Peninsula in the southwestern part of the country. As we went over the highest pass on the Cerro de la Muerte, we stopped briefly on the roadside in Tapanti National Park to see some of the plants characteristic of the páramo. The páramo is the ecosystem of the regions above the treeline and below the permanent snowline in the northern Andes of South America and adjacent southern Central America. This high, tropical montane vegetation is composed mainly of rosette plants, shrubs and grasses. The weather is generally cold and humid, but it can fluctuate suddenly and dramatically. The páramo in Costa Rica is a dwarf forest, dominated by the dwarf bamboo Chusquea subtessellata, together with short trees in the genus Escallonia, and low shrubs and herbs, many of which are endemic to the mountain top.

Trailhead in Tapanti National Park (L), Dave photographs the endemic thistle (LC), thistle head (RC), and dwarf bamboo Chusquea subtessellata (R).

At slightly lower elevations the dominant vegetation type is oak forest with a bamboo understory (or was, before they were cleared to provide pasture and agricultural land) with a whole other set of interesting endemic plants that thrive in the cool temperatures and clouds that envelop the forests at this elevation.

Senecio sp. blooming on roadside (L), purple flower (LC), Calceolaria sp. (RC) and tubular red and yellow flowers on a vine with cucumber-like leaves (R).

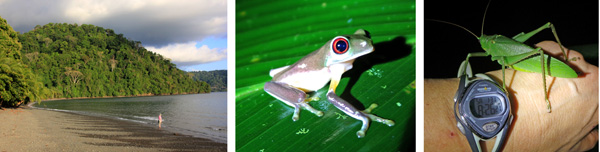

Only a relatively few miles away as the crow flies, but worlds away in climate and vegetation type is the Osa Peninsula. Once connected to the area that is now Columbia, before continental drift and rising sea levels cut it off, the plants here have more affinities with South American flora than anything to the north. This is one of the last truly wild places in Costa Rica, preserved in the huge Corcovado National Park and many private reserves. We drove as far as Golfito, but then had to go another half hour to reach our remote lodge immersed in the rainforest along the coast of the Golfo Dulce, accessible only by boat. Fortunately the weather was good while making the journey in two small, only partially covered motor boats. Our arrival was heralded by the squawking of scarlet macaws in the beach almond and wild cashew trees on the beach.

Golfo Dulce (L), part of the group on the boat to the lodge (C), and macaws in the wild cashew tree on the beach – they blend in surprisingly well despite their bright colors (R).

The buzzing of insects, tinking and chirping of frogs, screeching calls of birds, and the deep rumble of howler monkeys was the sound track as we explored the trails around the lodge before a dramatic thunderstorm rolled through at happy hour, with a torrential downpour as we were enjoying piña coladas and Thai mojitos (made with basil and ginger instead of mint) in the open air bar. Despite the weather we managed to find a number of interesting critters that night after the rain had moved through.